From disabling injury, a life of saintly inspiration

He was the finest athlete I ever saw up close, certainly the best I ever played against. I got to know him in high school, where he was a varsity baseball player. I sat right behind him in homeroom for two of our four years at Monsignor Bonner High School in Drexel Hill, because of the alphabet. He was Atkinson; I was Barone.

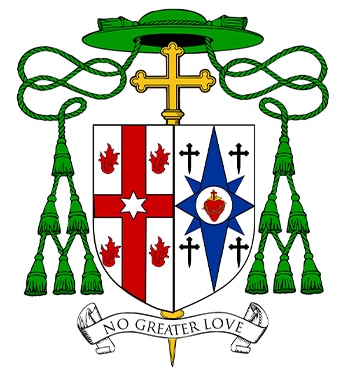

He was unassuming and good-natured, but not the sort of person who would up and decide to become a priest. When he up and decided to become a priest, I was surprised. I had up and decided the same thing, and our connection continued in the Augustinian seminary.

This is where we played, mainly touch football. He was fast, gifted with ridiculous reflexes, and able to catch anything thrown near him. The one time I was sure I would tag him, we were playing in a downpour. He pulled the football out of the air, tucked it away, and watched me angling toward him at top speed. The muck was too slick to permit his escape.

So he went into a slide, sort of as if he were on a skateboard. I yelled something unpriestly as I ran harmlessly past him; he loped into the end zone.

Our rooms faced each other, so we could look across the corridor and chat, a forbidden activity we indulged in daily. One especially gloomy evening I revealed all the anxiety and grief I was then suffering. “How do you handle it when everything is going wrong?” I asked him.

His response was swift and completely unexpected. “I just look up,” he answered, glancing at the ceiling, “and say, ‘Thy will be done.’ ”

During our second year, our novitiate, he stopped playing ball forever. He was thrown from a toboggan after the season’s final snowfall. His forehead fiercely smacked a skinny tree, and he was paralyzed.

At the hospital he was pronounced terminal. “He won’t live out the night,” his doctors said, unaware that, although he couldn’t move a muscle and was temporarily blind, he could hear just fine. For example, for the first time in his life he heard the word quadriplegic.

The doctors did him an unintended favor. Their casual dismissiveness, combined with their heroic efforts to stabilize him, gave him one, only one, area of control. He could prove them wrong. He could live.

And he did.

Read more at Philly.com…